Item : 372339

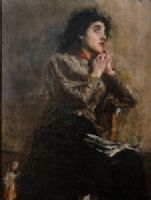

Antonio Mancini (1852-1930) "The Model (Desire)"

Author : Antonio Mancini

Period: Second half of the 19th century

The Model (Desire) by Antonio Mancini

Oil painting on canvas from the second half of the 19th century.

signed in the lower left in red A. Mancini Roma

Dimensions: cm h 100 x 75

Antonio Mancini (1852 Rome - 1930 Rome)

In the same year as Mancini's birth, the family moved to Narni. Here he received his initial education from the Piarists at the church of S. Agostino. Encouraged by the Counts Cantucci, who recognized his talent for art, Paolo sent his son to work with a local decorator and soon, in 1865, probably to start him on good artistic studies, he decided to move with the whole family (his wife and three children, Mancini, Giovanni and Angelo) to Naples. Immediately employed as a gilder in a workshop in Vicolo Paradiso, "near the house of Giacinto Gigante" (from the Autobiographical Notes dictated by Antonio Mancini to his nephew Alfredo in the years 1925-1930, transcribed in Santoro, p. 257), Mancini was placed in the school at the Oratory of the Girolamini and simultaneously attended evening classes at the church of S. Domenico Maggiore, where he met and began to associate with his contemporary Vincenzo Gemito; at the studio of the sculptor Stanislao Lista, they made it a habit to draw from antique casts and above all 'from life', portraying occasional models found in the street and depicting each other. The small monochrome depicting a Young Naked Scugnizzo (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection) seems to refer to this moment. In July 1865 he enrolled at the Institute of Fine Arts in Naples (his teachers in the figure drawing school were Raffaele Postiglione and Federico Maldarelli), obtaining the first prize in the figure school the following year. Like Gemito, Mancini was not content to try his hand at academic subjects, but turned his gaze to the surrounding reality, taking inspiration from the spectacle of popular life; the world of the circus, in particular, provided him with decisive suggestions. Domenico Morelli's arrival to the chair of painting at the Institute in 1868 represented a fundamental stage in Mancini's training, who, although extraneous to Morelli's main creative and thematic tendencies, would have shared with the master, critically absorbing the anti-academic orientation of his teachings, the need for an art firmly based on formal values. Prompted by Morelli, Mancini had the opportunity to train himself on the great Neapolitan painting of the seventeenth century, thoroughly assimilating the lesson of Neapolitan naturalism in the churches and museums of the city. With Francesco Paolo Michetti, who also arrived in Naples in 1868 from Chieti, as well as with Gaetano Esposito and Paolo Vetri, Mancini formed a strong and incisive bond of life and work during the fundamental years of study in Naples. If Mancini's first dated work (Head of a Girl, 1867: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) still proves to be a work of no significant depth, the following year he made his debut with an authentic masterpiece, Lo scugnizzo or Third Commandment (Antonio Mancini, p. 95 n. 1), depiction of a ragged and destitute adolescent contemplating the remains of a worldly feast, whose opulent gaiety (evoked only through details of still life) is close to the young man yet intangible for him, vulgar yet enviable. The work was then exhibited in 1875 at the Promotrice in Naples, and must be considered, with After the Duel (Turin, Civica Galleria d'arte moderna: ibid., pp. 95 s. n. 2), an incunabulum of Mancinian poetics, rich in pictorial means and strongly evocative in thematic choices. A prodigious testing ground for the sixteen-year-old artist, it was in fact immediately admired by Lista and Filippo Palizzi, who saw it in Mancini's first studio, obtained "in the attic of a nearby house" (Santoro, p. 257), in vicolo S. Gregorio Armeno. With this genre of production, the predilection for the representation of the Neapolitan scugnizzi began, whose childhood denied by the miserable living conditions is described with intense realism and at the same time transfigured in a mythical key. The intimate moral identification with the world of the excluded does not in fact imply an adherence to the expressive cadences of social denunciation, but rather becomes a vehicle of poetic and psychological sublimation (see Carminella, 1870: Rome, Galleria nazionale d'arte moderna; Il prevetariello, 1870: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte; Il cantore, 1872: The Hague, National Museum H.W. Mesdag; Saltimbanco, 1872: New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Bacchus, 1874: Milan, Museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnica). At the beginning of the eighth decade, in the wake of his success at the Institute of Fine Arts - in 1870 he won the first prize for painting; the following year, that of figure drawing with Dressing the Nudes (Naples, Accademia di belle arti) - and thanks to the interest of Antonio Lepre, doctor and teacher of anatomy at the same institute, Mancini obtained some premises in the former convent of the church of S. Andrea delle Monache which he used as a studio together with Gemito, the sculptor Michele La Spina of Acireale and the painter Vincenzo Volpe. There he created, in 1871, the Figure with Flowers on her Head which, exhibited at the Promotrice in Naples, made him known to the Belgian musician Albert Cahen, who requested a replica. Younger brother of Édouard, an influential financier based in Rome, Albert Cahen soon became a true patron for Mancini; this is the first of those numerous patronage links that would constitute a constant feature of the artist's entire professional career, characterising his relationship with clients - always conditioned by a material dependence which was by now unusual for the times - in a strongly anti-modern key (Rosazza). Through Cahen, Mancini came into contact with figures from cosmopolitan learned society (including the writer Paul Bourget and the Curtis family) who greatly appreciated and supported his output. After the failure of an attempt to bring Mancini closer to the German merchant G. Reitlinger, supporter of other southern painters, Cahen provided Mancini with contacts with the international art market, which allowed him to send paintings to Alphonse Portier, who was able to guarantee the sale of some works. Also through Cahen, Mancini gained access to the Parisian Salons, where he sent Dernier sommeil and Enfant allant à l'école in 1872 and Orfanella (Amsterdam, National Museum) in 1873, already rejected, due to its large size, by Giuseppe Verdi, who had seen it in Naples (Santoro, p. 257). The first important study trip dates back to 1873: in May he visited Venice, where he joined Cahen, and subsequently Milan, at whose National Exhibition of Fine Arts he exhibited two small-format works initially discarded by the commission, but then re-inserted into the exhibition in prominent positions by the organiser Eleuterio Pagliano. In the summer of 1874, with Gemito, Michetti and Eduardo Dalbono, Mancini assiduously frequented the Villa Arata in Portici, where from July he resided with the family of Mariano Fortuny, in the months immediately following Fortuny's sudden death, which occurred in Rome on 14 November of that year (Picone Petrusa, p. 426). The encounter, fundamental - as for the other Neapolitan artists - because of the extraordinary pictorial and aesthetic suggestions triggered by the frequentation of the Spanish master, represented for Mancini the possibility of finally becoming known to Adolphe Goupil, the famous French merchant supporter of the most vibrant pictorial and decorative talents of the moment. The work Jeune garçon tenant une pièce de monnaie of 1873-74 (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection: A chisel and a brush, p. 70 n. 18), a gift from Mancini to Fortuny, was in fact part of the famous auction sale of the Spanish artist's collection, which took place in Paris in 1875, precisely by Goupil. Following this opportunity for strong visibility, Mancini was urged to go to Paris, where he stayed from May to September (1875) and where he was able to meet and associate not only with Italian artists active in the French capital, such as G. De Nittis and Giovanni Boldini, but also with Ernest Meissonier and Jean-Léon Gérôme. From the Parisian merchant Mancini obtained a contract that would allow him not to reside in Paris, but to send works from Naples; although the catalogue of the Salon of 1876, where Le petit écolier (Paris, Musée d'Orsay) was exhibited, states that he resided at Goupil's, Mancini was in fact back in Naples that year. An unsuccessful attempt to open a market in Rome (where he stayed briefly at the Circolo degli Artisti) and, above all, the poor success at the Neapolitan National Exhibition of 1877 (where he exhibited Love your neighbour as yourself and The children of a worker) nevertheless induced him to attempt a new experience in France, and in March 1877 he was again in Paris, with Gemito. According to Cecchi (pp. 85 s.) Mancini brought with him to France the most significant of the paintings dedicated to the depiction of Neapolitan scugnizzi, the Saltimbanco (Philadelphia, Museum of Art, Jordan bequest) in costume with peacock feather, executed in Naples "in the shadow of a candle directed by Gemito" and masterpiece of extraordinary poetic synthesis of the artist. Arriving in Paris damaged, the painting was retouched by Mancini himself (1878) who for this purpose had Luigi Gianchetti, known as Luigiello, a young scugnizzo who had become his favourite model, brought from Naples. The saltimbanco, initially purchased by Cahen, was then exhibited at the Italian section of the 1878 Universal Exhibition and there purchased by the committee of the Exhibition (Antonio Mancini, p. 101 n. 13). The economic pact that Mancini made in Paris with Gemito dates back to these years, a sort of protectionist agreement that should have prevented both from selling their works without the other's consent regarding the sale price. This pact, disadvantageous for both, generated a series of bitter conflicts that led, in 1878, to the painful breakdown of the friendship with the sculptor. The disagreements with Gemito, moreover, foreshadowed a general worsening of the Parisian experience, marred by debts, illnesses as well as the difficult integration into the demanding environments of local social life. With the bitterness of a personal failure, Mancini therefore returned to Naples in March 1878. The already precarious psychic equilibrium was definitively disturbed in the following months and, although he continued to paint (La corallaia; Casa di pegni; Si vende), Mancini was subject to repeated nervous breakdowns (Oliverio). Entrusted to the care of Professor Giuseppe Buonomo in 1881, he was interned in the provincial asylum of Naples. Not even in the months spent in the asylum, from October 1881 to February 1882, did Mancini cease to paint; the Portrait of Doctor Buonomo, the Portrait of Doctor Cera, several portraits of asylum staff, as well as numerous self-portraits - a genre in which he never tired of trying his hand - in which Mancini scrutinised himself with acuity in a sort of ruthless autobiography of his mental states (Antonio Mancini, pp. 104 s. n. 19, 116 s. nn. 41 s.). In addition, testimony to his state of turmoil is an overflowing graphomania which manifested itself in endless and disconnected letters sent to friends and acquaintances (partially consultable only in Santoro). Discharged from the care facilities and financially aided by Baron Carlo Chiarandà, Mancini decided to leave Naples for Rome, a city where he moved permanently in 1883, also supported by a small monthly subsidy offered by the Institute of Fine Arts through the interest of Palizzi and Morelli. The beginning of the partnership with Marquis Giorgio Capranica del Grillo, son of Giuliano and of the actress Adelaide Ristori (in 1889 he executed the portrait of him now at the National Gallery in London), a leading exponent of the Roman cultural environment, who became his patron and guardian, also dates back to 1883. Shortly afterwards he met Daniel Sargent Curtis, a wealthy American patron, who settled in Venice in Palazzo Barbaro, and his painter son, Ralph Wormsley Curtis, cousin of John Singer Sargent; with the works sent for their Venetian residence, Mancini entered the circuit of foreign collectors residing in Italy, an important strand of commissions throughout his life. This was followed by the meeting with the sculptor Thomas Waldo Story, son of the more famous William Wetmore Story, an American who had settled permanently in Rome in 1851, who offered him the opportunity to work in his studio located in the family palace in via San Martino della Battaglia. On the other hand, the relationship with the marine painter, banker and Dutch patron Hendrik Willem Mesdag, who from 1885 began to collect Mancini's works, now largely collected in the museum of the same name in The Hague (such as Il ragazzo nudo of 1885: Pennock and Italie 1880-1910), always remained a relationship at a distance. In 1887, present in Venice for the National Exhibition, Mancini frequented the salon of Palazzo Barbaro, where the Curtises entertained a cultural circle. Back in Rome, Mancini experimented in an increasingly conscious way with the so-called double grid system, consisting of a pair of string-squared frames placed in front of the model and in front of the canvas to guarantee the accuracy of the perspective layout. Left visible below the pictorial material, it gave rise to the well-known squared effect typical of his painting between the late eighties and nineties: an effect initially appreciated but gradually regarded with suspicion by critics who would end up stigmatising its excessive use. Although the intensity of his technical-pictorial research had given new impetus to his production, Mancini continued to remain in a marginalised position in the Roman artistic environment, which he himself on several occasions deprecated as corrupt and vulgar (Santoro, p. 192); he maintained his life within the coordinates of a precarious and unregulated existence and was forced several times to ask his high-ranking friends for help in order to obtain some assignment (ibid., p. 204). Despite these conditions, his father Paolo, who had become a widower, moved to Rome from 1890 to live with Mancini, becoming one of his most habitual models (Antonio Mancini, pp. 110 s., nn. 29-39). In 1894 he obtained from the economist Maffeo Pantaleoni the commission for the portrait of his mother (Portrait of Signora Pantaleoni, 1894: Rome, Galleria nazionale d'arte moderna), later presented and awarded at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1900; while in 1895 he managed to expand his circle of clients by meeting Isabella Stewart Gardner (Licht, p. 11), present in Rome in the spring with her husband, who - already in possession of the Ciociaretto portastendardo previously belonging to the Curtises - commissioned him to paint the portrait of her husband, to be executed in Venice, where the family would be guests in Palazzo Barbaro. Mancini in fact reached them in May, in time to visit the first International Art Biennale (where he exhibited Roman Boy and Ophelia), an exhibition in which he would regularly participate until 1914. The meeting with Edoardo Almagià, which took place in 1898, generated new significant commissions not only from him (Portrait of the Almagià family, 1903), but also from important families related or linked to him, such as the Ambrons, the Bondis, the Volterras, the Sonninoss. In 1901, on the wave of the great success obtained in Paris with the Portrait of Signora Pantaleoni, Claude Pensonby, a friend of the Curtises and Sargent, invited Mancini to go to London, where the artist arrived in June of the same year and where he would return in 1907. Arriving in London, in 1901 Mancini executed the Portrait of Claude Pensonby and the Portrait of Haroldino Pensonby. And he met Mary Hunter, sister of the composer Ethel Smith and a good friend of Sargent. This refined protagonist of European cultural circles became a careful protector of Mancini. His portrait, that of her husband Charles and that of their daughter Sylvia, all painted in the family home in Selaby, in Darlington, date from the autumn of 1901. In London, Mancini also frequented the artistic-literary salon of the Caccamisi family; there he had the opportunity to meet Jacques-Émile Blanche, Auguste Rodin, John Lavery as well as John S. Sargent, the contiguity with whom is also demonstrated by the portrait of Mancini executed by the American artist in 1902 (Rome, Galleria nazionale d'arte moderna). Disappointing, despite the good contacts, was Mancini's arrival at the awaited annual exhibition of the Royal Academy, where only one (the Portrait of Mary Hunter) of the four paintings presented was accepted; disappointed also by the lack of support from Sargent, Mancini returned to Italy, stopping in Ghiffa, on Lake Maggiore, in view of the portrait to be made to the Torelli spouses, wealthy collectors of contemporary art and particularly of works of the Lombard Scapigliatura. In the meantime, signals of international success began to arrive and, after the monographic exhibition organised in 1897 by Mesdag at the Pulchri Studio Association of The Hague (repeated in 1902), the presentation of seventeen of his works at the Dordrecht exhibition in 1899, the success obtained in Munich with the Portrait presented at the International Exhibition, Mancini also participated in 1904 at the International Exhibition of Düsseldorf with Boy with Shells (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection) and The gifts of the grandfather; while the Portrait of Giorgio Capranica del Grillo and the Portrait of Signora Pantaleoni will be awarded respectively at the Universal Exhibition in Saint Louis (1904) and at the International Exhibition in Munich (1905). In Rome, meanwhile, Mancini came into contact with new clients such as Hugh Lane, director of the Municipal Gallery of Dublin. A friend of the Hunters, passing through Rome in 1905, Lane visited the artist's studio, starting negotiations for the purchase of his works (Portrait of Giorgio Capranica del Grillo), as well as for the commission of his own portrait, executed in 1906, which earned Mancini a new invitation to reach England. Again in London in September 1907, still in close contact with the Hunter family (Portrait of Phyllis Williamson, daughter of Mary Hunter; Portrait of Elizabeth and Charles Williamson; Portrait of Elizabeth Williamson), Mancini was then in York, guest of the Lawson family (Portrait of Ambassador Thomas Lawson, husband of Sylvia Hunter), and, finally, in Dublin, guest of Hugh Lane, through whom he came into contact with the local literary and artistic society. Back in London, he realised a series of portraits for the aristocratic Dixwell Oxenden family (Portrait of Sir Basil Heneage Dixwell Oxenden, 1908: Rome, private collection) and the three paintings making up the series To my Lord. Returning to Rome in the summer of 1908, Mancini signed a contract with the German merchant Otto Messinger (Portrait of Otto Messinger, 1909: Rome, Galleria nazionale d'arte moderna), already a collector of southern painters, who first hosted him in Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne and then set up a personal studio for him in the Corrodi houses in via Maria Adelaide, near Piazza del Popolo. Here, adapting to the client's requests, he painted almost exclusively figures in eighteenth-century or exotic costumes, knights, halberdiers, musicians, always relying on Messinger's resources for the supply of sumptuous costumes, furnishings and models. Still following his wealthy client, in 1910 he undertook an important trip to Germany, staying in Munich, where he met Franz von Stuck, and visiting Nuremberg, Cologne, Berlin. At the beginning of 1911, after the exhibition of Messinger's collection in Munich, Mancini, passing through the Netherlands without meeting Mesdag, returned to Rome. In 1911 he participated in the International Exhibition, with eight of the works painted for Messinger which earned him one of the five ex aequo prizes for the best artist. Critics paid particular attention to Mancini's technique, of ever greater chromatic and material audacity (Ozzola). Among the first to congratulate on the success obtained at the Rome exhibition was Fernand du Chêne de Vère, a wealthy French industrialist transplanted to Milan, who replaced Messinger, with whom the relationship had ended, proposing to Mancini an exclusive contract renewed annually from 1912, immediately after the death of his father Paolo, until 1918. During this period Mancini lived in the residence prepared for him by his patron at Villa Jacobini in Frascati, where he had ample space and a very rich arsenal of canvases, paints, fabrics, original costumes, furnishings of all kinds for his eccentric and exotic settings. Only at the end of the World War, having learned that his brother Giovanni and his nephew Alfredo, returning from the front, were in Rome, he decided to leave the villa to move to his brother Giovanni and his family, first in an apartment in Viale Liegi and then, from 1926, in the villa in Via delle Terme Deciane, his last residence. In 1920 the XXII Venice Biennale definitively consecrated his triumph, dedicating a personal exhibition to him, all composed of recent works (Head of a woman in blue, Self-portrait, Enrica, Ciociara, Reflections, Satanic, Profile, Girl, Head of a woman, Portrait of Lieutenant Bonanni, Page, In the garden, My niece, Embroidery, Flag, Portrait, Smile, Gentleman of the seventeenth century, Spring, Winter, Shells), purchased en bloc and at high price by a group of art dealers. The regained economic security allowed him to repurchase the youthful painting Lo scugnizzo (Third Commandment), returned from France where it had been part of the Parisian collection of Michele Manzi and re-proposed at the auction organised by Augusto Jandolo in February 1921. The last years of Mancini's life were marked by important tributes in the main Italian exhibitions. In 1927 his seventy-fifth birthday was officially celebrated with a retrospective exhibition at the Augusteo in Rome promoted by the magazine La Fiamma; in Milan, in the same year, a sale of over forty works, presented in the catalogue by Vittorio Pica, belonging to the Chêne de Vère collection, took place at the Pesaro gallery. This was followed by the exhibition organised in 1923 at the Castello Sforzesco, dedicated to the Frascati period. In London, the Knoedler gallery in Bond Street organised at the end of 1928 an exhibition of twenty-seven paintings and thirteen pastels of the English period, in whose catalogue the phrase of Sargent was prefixed: 'I have met in Italy the greatest living painter'. Appointed academician of merit of S. Luca in 1913, honorary citizen of Naples in 1923 with a solemn ceremony at Palazzo S. Giacomo (on that occasion he met again and for the last time Gemito), on 29 October 1929 he was among the first to be welcomed into the newly established Reale Accademia d'Italia. In the same year he executed the Self-Portrait (private collection) on which he annotated, in a sort of disconnected biographical palimpsest, the main scansions of his professional and existential path (Antonio Mancini, p. 128). Among the last works painted before his death, the Self-Portrait with a Red Turban (private collection). Mancini died in Rome on 28 December 1930. A personal exhibition of three rooms organised by Cipriano Efisio Oppo (about fifty works) solemnly honoured him at the I Rome Quadriennale in 1931. In 1935 Mancini's remains were moved from the Verano to the church of S. Alessio on the Aventine.

Sources and Bibliography:

L. Ozzola, Contemporary Artists: Antonio Mancini, in Emporium, XXXIII (1911), pp. 415-429.

D. Cecchi, Antonio Mancini, Turin 1966.

E. Santoro, La poetica di Antonio Mancini attraverso gli appunti e le lettere, thesis, University of Bologna, faculty of letters and philosophy, a.a. 1976-77.

H. Pennock, Antonio Mancini en Nederland, Haarlem 1987.

Antonio Mancini, 1852-1930 (catalogue, Spoleto), edited by B. Mantura - E. di Majo, Rome 1991.

A. Oliverio, Il pittore pazzo, ibid., pp. 37-41.

P. Rosazza, Fortuna di Antonio Mancini nelle raccolte pubbliche e private, ibid., pp. 29-35.

M. Picone Petrusa, Dal 1848 alla fine del secolo, in Civiltà dell'Ottocento. Le arti a Napoli dai Borbone ai Savoia (catalogue), I, Naples 1998, pp. 425-433.

A chisel and a brush. Vincenzo Gemito e Antonio Mancini. Italian art 1850-1925 from the Gilgore Collection (catalogue, Naples, FL), edited by F. Licht, s.l. 2000, p. 70 n. 18.

F. Licht, Mancini and Gemito in the Gilgore Collection, ibid., pp. 11-28.

Italie 1880-1910. Arte alla prova della modernità (catalogue, Rome-Paris), edited by G. Piantoni - A. Pingeot, Turin-London 2000, pp. 105 s. n. 6.