Item : 372315

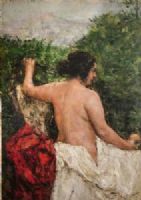

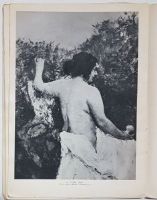

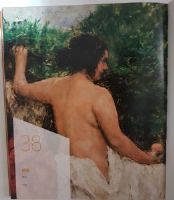

Antonio Mancini, "Nude Woman 1926"

Author : Antonio Mancini

Period: Early 20th century

Nude by Antonio Mancini.

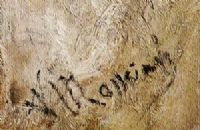

Signed in black on the lower right: A. Mancini

Oil painting on canvas from 1926

Measurements: cm h 140 x 100

Some publications are attached.

The main theme of Mancini's work is the human being and its real and truthful reproduction, but not objective, but always subjectively linked to the pathos and identification of feeling, which unites us as participants in the same emotional and human experience. The pictorial and graphic production focuses almost exclusively on the representation of the human figure and corporeality, with a preponderance of female subjects. This physicality is particularly sought after for Mancini's predisposition to the use of color and his innate plastic sense. Sometimes the material is treated with such mastery as to deceive the eye and appear almost three-dimensional and sculptural. The human body is the reality and the material that we can all know best, as we can only have full experience of our own existence and solidity, and not of that of others around us, of which we can only have partial sensory knowledge. For Mancini, whose research was based on the study and reproducibility of truth and light, which makes up knowable matter, it is therefore spontaneous to focus on the representation of the human body.

Mancini will treat the theme of nudity in a totally innovative light, hardly recognizable by an inexperienced eye, in a way totally devoid of pornographic sensuality, with an ironic and provocative feeling; his nudes are an affront to the voyeur of pornography hidden behind the firm buttocks in Turkish baths and the turgid breasts under the soft hair of the saints. Mancini offers children on silver platters and fat ladies in the foreground. His is a criticism, even if not entirely consciously sought, of art as a pornographic expedient, not a tribute, and if the observer is not struck by it, it is only due to his own lack of sophistication, which a more cultured audience would immediately notice.

Mancini does not propose a nudity that offends human ethics, he proposes a nude that directly upsets the soul, the feelings of the observer, because the truth is offered with the intention of undressing as no one had ever undressed before, he does not only undress his subject, he undresses the observer himself. The nude is nothing more than the earthly body of man driven from earthly paradise, a body corrupted by sin, which cannot be masked or hidden in any way; unhideable, because it is deprived of the grace of God, naked before its own being human, real. Nude which is not impudent, it is earthly, carnal, true. Thus the observer's identification with Mancini's real representation is triggered, which is the innovation of his subjects: whether dressed or undressed, they break down that wall that had always been erected between user and mimesis, creating an emotional bridge towards the observer who in front of his paintings no longer feels estranged, as in front of a mere representative image, more or less allegorical, until then the only pictorial intention or the only possible talent.

Moreover, these are years of great events: the Crimea, Magenta, the Expedition of the Thousand, Milazzo[1] and little Antonio often finds himself in contact with French, Swiss and Papal soldiers. He experiences these events in a distant way, but these memories will return in his paintings; when, in adulthood, he will paint his father wrapped in a tricolor flag, remembering him while he anxiously awaited the entry of the Piedmontese. Memories that will make their way, even if only unconsciously, into Mancini's attitudes and pictorial manner, which often recalls the tricolor in his paintings or inserts references to the homeland and pride of his origins; defining himself as Roman and remarking his fortuitous birth in the capital.

[1] 1859: Second War of Independence.

Antonio Mancini (1852 Rome - 1930 Rome)

In the same year as Mancini's birth, the family moved to Narni. Here he received his first education from the Piarists of the church of S. Agostino. Urged by the Counts Cantucci, who recognized his predisposition to art, Paolo sent his son to work with a local decorator and soon, in 1865, probably to start him on good artistic studies, he decided to move with his whole family (his wife and three children, Mancini, Giovanni and Angelo) to Naples. Immediately employed as a gilder in a workshop in Vicolo Paradiso, "near the house of Giacinto Gigante" (from the Autobiographical Notes dictated by Antonio Mancini to his nephew Alfredo in the years 1925-1930, transcribed in Santoro, p. 257), Mancini was put into school at the oratory of the Girolamini and simultaneously attended evening school at the church of S. Domenico Maggiore, where he met and began to frequent his contemporary Vincenzo Gemito; at the studio of sculptor Stanislao Lista they took the habit of drawing from ancient casts and above all from life, portraying occasional models found in the street and depicting each other. It seems that the small monochrome depicting a Young Naked Scugnizzo (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection) should be referred to this moment. In July 1865 he was enrolled in the Institute of Fine Arts in Naples (his teachers in the drawing school were Raffaele Postiglione and Federico Maldarelli), obtaining the first prize of the figure school as early as the following year. Like Gemito, Mancini was not content to try his hand at academic themes, but turned his gaze to the surrounding reality, drawing inspiration from the spectacle of popular life; the world of the circus, in particular, provided him with decisive suggestions. Domenico Morelli's arrival at the chair of painting at the institute in 1868 represented a fundamental stage in Mancini's education, who, although foreign to the main creative and thematic trends of Morelli, would have shared with the master, critically absorbing the anti-academic orientation of his teachings, the necessity of an art firmly based on formal values. Urged by Morelli, Mancini had the opportunity to train himself on the great Neapolitan painting of the seventeenth century, thoroughly assimilating the lesson of Neapolitan naturalism in the churches and museums of the city. With Francesco Paolo Michetti, who also arrived in Naples in 1868 from Chieti, as well as with Gaetano Esposito and Paolo Vetri, Mancini made a strong and incisive bond of life and work during the fundamental years of study in Naples. If Mancini's first dated work (Head of a Girl, 1867: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) still proves to be an insignificant test, the following year he made his debut with a true masterpiece, Lo Scugnizzo or Third Commandment (Antonio Mancini, p. 95 n. 1), a depiction of a ragged and disinherited adolescent contemplating the remains of a worldly feast, whose opulent gaiety (evoked only through still life details) is close to the young man and yet intangible for him, loud yet enviable. The work was then exhibited in 1875 at the Promotrice di Napoli, and is to be considered, with Dopo il duello (Turin, Civica Galleria d'arte moderna: ibid., pp. 95 s. n. 2), an incunabulum of Mancini's poetics, rich in pictorial means and strongly evocative in thematic choices. A prodigious test bench for the sixteen-year-old artist, it was in fact immediately admired by Lista and Filippo Palizzi who saw it in Mancini's first studio, obtained "in the attic of a nearby house" (Santoro, p. 257), in Vicolo S. Gregorio Armeno. With this kind of production, the predilection for the representation of Neapolitan scugnizzi began, whose childhood denied by the miserable living conditions is described with intense realism and at the same time transfigured in a mythical key. The intimate moral identification with the world of the excluded does not in fact imply an adherence to the expressive cadences typical of social denunciation, becoming rather a vehicle of poetic and psychological sublimation (see Carminella, 1870: Rome, Galleria nazionale d'arte moderna; Il prevetariello, 1870: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte; Il cantore, 1872: The Hague, H.W. Mesdag National Museum; Saltimbanco, 1872: New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Bacco, 1874: Milan, Museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnica). At the beginning of the eighth decade, in the wake of the good successes at the Institute of Fine Arts - in 1870 he obtained the first prize for painting; the following year, that of the figure drawing with Vestire gli ignudi (Naples, Accademia di belle arti) - and thanks to the interest of Antonio Lepre, doctor and teacher of anatomy in the same institute, Mancini obtained some premises in the former convent of the church of S. Andrea delle Monache which he used as a studio together with Gemito, the sculptor Michele La Spina of Acireale and the painter Vincenzo Volpe. There, in 1871, he created the Figura con fiori in testa which, exhibited at the Promotrice di Napoli, introduced him to the Belgian musician Albert Cahen, who requested a copy. Albert Cahen, the younger brother of Édouard, an influential financier based in Rome, soon became a true patron for Mancini; this is the first of those numerous patronage links that would constitute a constant of the artist's entire professional career, characterizing his relationship with the client - always conditioned by a material dependence that was now unusual for the times - in a strongly anti-modern key (Rosazza). Through Cahen, Mancini came into contact with figures from cosmopolitan cultured society (including the writer Paul Bourget and the Curtis family) who greatly appreciated and supported his production. When the attempt to bring Mancini closer to the German merchant G. Reitlinger, a supporter of other southern painters, failed, Cahen provided Mancini with contacts with the international art market, which allowed him to send paintings to Alphonse Portier who was able to guarantee him the sale of some works. Again through Cahen, Mancini gained access to the Parisian Salons, where in 187