Item : 372311

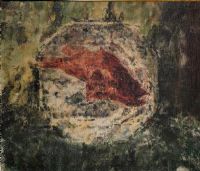

Antonio Mancini. "Grouper on plate or Scorpion fish on plate" about 1900.

Author : Antonio Mancini

Period: Early 20th century

"Grouper on plate or Scorpion fish on plate" by Antonio Mancini. Signed in red on the upper left: A. Mancini. Oil on canvas painting from around 1900 in excellent condition. Executed around 1900. Dimensions: cm h 60 x 70. Antonio Mancini almost never paints animals, and if he does, they are far from the style of the Neapolitan realist painters of the time, like Morelli or Palizzi. In the rare examples of Mancini's animals, they are decorations linked to human reality, almost objects surrounding real life; like the scorpion fish, it is a fish, but flattened, it is not in a glass bowl, as many believe, it is on the plate, it constitutes decoration. As with landscapes, still lifes and animals, which appear in Mancini's paintings, are always an expression of humanity, hidden within them, always present even in its total absence. Antonio Mancini (1852 Rome - 1930 Rome) In the same year as Mancini's birth, the family moved to Narni. Here he received his early education from the Piarists of the church of S. Agostino. Prompted by the Counts Cantucci, who recognized his predisposition to art, Paolo sent his son to work with a local decorator and soon, in 1865, probably to get him started with good artistic studies, he decided to move with the whole family (his wife and three children, Mancini, Giovanni and Angelo) to Naples. Immediately employed as a gilder in a workshop in vicolo Paradiso, "near the house of Giacinto Gigante" (from the autobiographical notes dictated by Antonio Mancini to his nephew Alfredo in the years 1925-1930, transcribed in Santoro, p. 257), Mancini was sent to school at the Oratory of the Girolamini and simultaneously attended the evening school at the church of S. Domenico Maggiore, where he met and began to frequent Vincenzo Gemito; at the studio of the sculptor Stanislao Lista they took the habit of drawing from ancient casts and above all from life, portraying occasional models found in the street and depicting each other. At this moment seems to refer the small monochrome depicting a Young barefoot boy (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection). In July 1865 he was enrolled in the Institute of Fine Arts in Naples (his teachers in the figure drawing school were Raffaele Postiglione and Federico Maldarelli), obtaining already the following year the first prize of the figure school. Like Gemito, Mancini was not content to try his hand at academic themes, but turned his gaze to the surrounding reality, taking inspiration from the spectacle of popular life; the world of the circus, in particular, provided him with decisive suggestions. Domenico Morelli's arrival at the chair of painting at the Institute in 1868 represented a fundamental stage in Mancini's formation, who, although extraneous to Morelli's main creative and thematic tendencies, would have shared with the master, critically absorbing the anti-academic orientation of his teachings, the need for an art firmly based on formal values. Encouraged by Morelli, Mancini had the opportunity to train in the great Neapolitan painting of the seventeenth century, thoroughly assimilating the lesson of Neapolitan naturalism in the churches and museums of the city. With Francesco Paolo Michetti, who also arrived in Naples in 1868 from Chieti, as well as with Gaetano Esposito and Paolo Vetri, Mancini formed a strong and incisive bond of life and work during the fundamental years of study in Naples. If Mancini's first dated work (Head of a Girl, 1867: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) still proves to be an insignificant proof, the following year he debuted with an authentic masterpiece, The Scugnizzo or Third Commandment (Antonio Mancini, p. 95 n. 1), a depiction of a ragged and disinherited adolescent contemplating the remains of a worldly feast, whose opulent gaiety (evoked only through details of still life) is close to the young man and yet for him intangible, brazen and yet enviable. The work was then exhibited in 1875 at the Promotrice of Naples, and is to be considered, with After the Duel (Turin, Civic Gallery of Modern Art: ibid., pp. 95 s. n. 2), incunabulum of the Mancini's poetics, rich in pictorial means and strongly evocative in thematic choices. Prodigious test bench of the sixteen-year-old artist, was in fact immediately admired by Lista and Filippo Palizzi who saw it in Mancini's first studio, obtained "in the suppigno of a nearby house" (Santoro, p. 257), in vicolo S. Gregorio Armeno. Began, with this kind of production, the predilection for the depiction of the Neapolitan scugnizzi, whose childhood denied by the miserable living conditions is described with intense realism and at the same time transfigured in a mythical key. The intimate moral identification with the world of the excluded does not, in fact, entail an adherence to the expressive cadences typical of social denunciation, but rather becomes a vehicle for poetic and psychological sublimation (see Carminella, 1870: Rome, National Gallery of Modern Art; Il prevetariello, 1870: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte; Il cantore, 1872: The Hague, National Museum H.W. Mesdag; Saltimbanco, 1872: New York, Metropolitan Museum of art; Bacco, 1874: Milan, National Museum of Science and Technology). At the beginning of the eighth decade, in the wake of the good successes at the Institute of Fine Arts - in 1870 he won the first prize for painting; the following year, that of figure drawing with Dressing the Nudes (Naples, Academy of Fine Arts) - and thanks to the interest of Antonio Lepre, doctor and anatomy teacher at the same institute, Mancini obtained some premises in the former convent of the church of S. Andrea delle Monache that he used as a studio together with Gemito, the sculptor Michele La Spina of Acireale and the painter Vincenzo Volpe. There he created, in 1871, the Figure with Flowers on her Head which, exhibited at the Promotrice of Naples, made him known to the Belgian musician Albert Cahen, who requested a replica. Younger brother of Édouard, an influential financier established in Rome, Albert Cahen soon became a true patron for Mancini; this is the first of those numerous patronage relationships that would constitute a constant of the artist's entire professional career, characterizing his relationship with the clientele - always conditioned by a material dependence now unusual for the times - in a strongly anti-modern key (Rosazza). Through Cahen Mancini came into contact with personalities of cosmopolitan cultured society (among others the writer Paul Bourget and the Curtis family) who greatly appreciated and supported his production. After the failure of the attempt to bring Mancini closer to the German merchant G. Reitlinger, a supporter of other Southern painters, Cahen provided Mancini with contacts with the international art market, which allowed him to send paintings to Alphonse Portier who managed to guarantee him the sale of some works. Also through Cahen, Mancini gained access to the Parisian Salons, where in 1872 he sent Dernier sommeil and Enfant allant à l'eacutecole and in 1873 Orfanella (Amsterdam, National Museum), already rejected, for its large size, by Giuseppe Verdi who had seen it in Naples (Santoro, p. 257). The first important study trip dates back to 1873: in May he visited Venice, where he reached Cahen, and then Milan, at whose National Exhibition of Fine Arts he exhibited two small-format works discarded in the first instance by the commission, but then reinserted in the exhibition in places of honor by the organizer Eleuterio Pagliano. In the summer of 1874, with Gemito, Michetti and Eduardo Dalbono, Mancini assiduously frequented the villa Arata of Portici, where from July resided with the family of Mariano Fortuny, in the months immediately before the sudden death of Fortuny, which occurred in Rome on November 14 of that year (Picone Petrusa, p. 426). The meeting, fundamental - as for the other Neapolitan artists - because of the extraordinary pictorial and aesthetic suggestions triggered by the frequentation of the Spanish master, represented for Mancini the possibility of finally being known by Adolphe Goupil, the famous French merchant supporter of the most lively pictorial and decorative talents of the moment. The work Jeune garçon tenant une pièce de monnaie of 1873-74 (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection: A chisel and a brush, p. 70 n. 18), a gift from Mancini to Fortuny, was in fact part of the famous auction sale of the Spanish artist's collection, which took place in Paris in 1875 under the care of Goupil. As a result of this occasion of strong visibility, Mancini was urged to go to Paris, where he stayed from May to September (1875) and where he had the opportunity to meet and frequent not only the Italian artists active in the French capital, such as G. De Nittis and Giovanni Boldini, but also Ernest Meissonier and Jean-Léon Gérôme. From the Parisian merchant Mancini obtained a contract that would allow him not to reside in Paris, but to send works from Naples; although in the catalog of the Salon of 1876, where Le petit écolier (Paris, Musée d'Orsay) was exhibited, Mancini is resident at Goupil's, Mancini was in fact in Naples again that year. An unsuccessful attempt to open a market in Rome (where he stayed briefly at the Circolo degli artisti) and, above all, the poor success at the Neapolitan National Exhibition of 1877 (where he exhibited Love your neighbor as yourself and The children of a worker) however induced him to try a new experience in France, and in March 1877 he was again in Paris, with Gemito. According to what Cecchi (pp. 85 s.) reported, Mancini brought with him to France the most significant among the paintings dedicated to the depiction of Neapolitan scugnizzi, the Saltimbanco (Philadelphia, Museum of art, Jordan estate) in costume with peacock feather, made in Naples "in the shadow of a candle directed by Gemito" and masterpiece of extraordinary poetic synthesis of the artist. Arrived in Paris damaged, the painting was retouched by the same Mancini (1878) who for this purpose had Luigi Gianchetti, called Luigiello, come from Naples, a young scugnizzo who had become his favorite model. The saltimbanco, purchased in the first instance by Cahen, was then exhibited at the Italian section of the Universal Exhibition of 1878 and purchased there by the Exhibition committee (Antonio Mancini, p. 101 n. 13). Dates to these years the economic pact that Mancini made in Paris with Gemito, a sort of protectionist agreement that should have prevented both from selling their works without the consent of the other regarding the sale price. This pact, disadvantageous for both, generated a series of bitter contrasts that resulted, in 1878, in the painful break of friendship with the sculptor. The disagreements with Gemito, moreover, were prodromal to a general deterioration of the Parisian experience, marred by debts, illnesses and the difficult insertion in the demanding environments of local social life. With the bitterness of a personal failure Mancini returned to Naples in March 1878. The already precarious psychological balance was definitively disturbed in the following months and, while continuing to paint (La corallaia; Casa di pegni; Si vende), Mancini was subject to repeated nervous crises (Oliverio). Entrusted to the care of Professor Giuseppe Buonomo in 1881 he was interned in the provincial asylum of Naples. Not even in the months spent in the asylum, from October 1881 to February 1882, Mancini stopped painting; belong to this moment the Portrait of Dr. Buonomo, the Portrait of Dr. Cera, several portraits of staff of the asylum, as well as numerous self-portraits - a genre in which he never tired of trying his hand - in which Mancini scrutinized himself with acuteness in a kind of merciless autobiography of his psychological states (Antonio Mancini, pp. 104 s. n. 19, 116 s. nn. 41 s.). Testimony to his state of turmoil is, moreover, an overflowing graphomania that manifested itself in endless and disjointed letters sent to friends and acquaintances (partially consultable only in Santoro). Released from the care institutions and financially helped by Baron Carlo Chiaranda, Mancini decided to leave Naples for Rome, the city where he moved permanently in 1883, supported also by a small monthly allowance offered by the Institute of Fine Arts for the interest of Palizzi and Morelli. 1883 also marked the beginning of the partnership with Marquis Giorgio Capranica del Grillo, son of Giuliano and actress Adelaide Ristori (in 1889 he executed his portrait now at the National Gallery in London), leading exponent of the Roman cultural environment, who became his patron and guardian. Shortly thereafter was the meeting with Daniel Sargent Curtis, a wealthy American patron, who settled in Venice in Palazzo Barbaro, and with his son the painter, Ralph Wormsley Curtis, cousin of John Singer Sargent; with the works sent for their Venetian residence, Mancini joined the circle of foreign collectors residing in Italy, an important strand of patronage throughout his life. This was followed by the meeting with the sculptor Thomas Waldo Story, son of the better known William Wetmore Story, American, permanently settled in Rome since 1851, who offered him the opportunity to work in his studio located in the family palace in via San Martino della Battaglia. Instead, the relationship with the marine painter, banker and Dutch patron Hendrik Will