Item : 229945

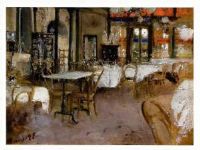

Antonio Mancini 1880 "Interior of the Vacca Cafe"

Author : Antonio Mancini

Period: Second half of the 19th century

Measures H x L x P

Height cm. : 24,5

Widht cm. : x

Deep cm. : 32,5

Interior of the Vacca Café by Antonio Mancini

Oil painting on panel from 1880. Measurements: cm h 24.5 x 32.5

Mancini paints landscapes, seascapes, interiors, and views from balconies and windows; he is a prolific and imaginative landscapist, both for the selection of his subjects and for the scenic and perspective choices he decides to make, which are almost photographic. As he describes, with decisive and robust brushstrokes, the features of the faces and clothing of his characters drawn from reality and traced with true force and light, so he manages to construct powerful views, where the light is ethereal and lives in absolute and real time, where there are no minutes or seconds but only the present, truer and more alive than ever. Devoid of people in the streets or sitting at the tables of the café, in the landscapes he avoids the human presence, almost distinguishing nature from man, so his scenarios are immersed in infinite time, where nothing can age and be consumed, but everything remains as it is and as it must be, true and real, forever.

Antonio Mancini (1852 Rome - 1930 Rome)

In the same year as Mancini's birth, the family moved to Narni. Here he received his initial education from the Piarists of the church of S. Agostino. Urged by the Counts Cantucci, who recognized his predisposition to art, Paolo sent his son to work for a local decorator and soon, in 1865, probably to start him on good artistic studies, he decided to move with the whole family (his wife and three children, Mancini, Giovanni, and Angelo) to Naples. Immediately employed as a gilder in a workshop in Vicolo Paradiso, "near the house of Giacinto Gigante" (from the autobiographical notes dictated by Antonio Mancini to his nephew Alfredo in the years 1925-1930, transcribed in Santoro, p. 257), Mancini was put in school at the oratory of the Girolamini and simultaneously attended evening school at the church of S. Domenico Maggiore, where he met and began to frequent his contemporary Vincenzo Gemito; at the studio of the sculptor Stanislao Lista, they took the habit of drawing from antique casts and especially from life, portraying occasional models found on the street and depicting each other. It seems that it is related to this moment, that the small monochrome depicts a young street urchin naked (Naples, FL, Gilgore collection). In July 1865, he was enrolled at the Institute of Fine Arts in Naples (his teachers in the figure drawing school were Raffaele Postiglione and Federico Maldarelli), and he obtained the first prize in the figure school the following year. Like Gemito, Mancini was not content with trying his hand at academic themes but turned his gaze to the surrounding reality, taking inspiration from the spectacle of popular life; the world of the circus, in particular, provided him with decisive suggestions. Domenico Morelli's arrival at the painting chair of the institute in 1868 represented a fundamental stage in Mancini's training, who, although alien to Morelli's main creative and thematic tendencies, would share with the master, critically absorbing the anti-academic orientation of his teachings, the need for an art firmly based on formal values. Prompted by Morelli, Mancini had the opportunity to train in the great Neapolitan painting of the seventeenth century, thoroughly assimilating the teaching of Neapolitan naturalism in the churches and museums of the city. With Francesco Paolo Michetti, who also arrived in Naples in 1868 from Chieti, as well as with Gaetano Esposito and Paolo Vetri, Mancini formed a strong and incisive bond of life and work during the fundamental years of study in Naples. If Mancini's first dated work (Head of a Girl, 1867: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) still proves to be an insignificant breath, the following year he debuted with a true masterpiece, Lo scugnizzo or Third Commandment (Antonio Mancini, p. 95 n. 1), depicting a ragged and disenfranchised adolescent contemplating the remains of a worldly feast, whose opulent gaiety (evoked only through details of still life) is close to the young man yet intangible for him, boisterous yet enviable. The work was then exhibited in 1875 at the Promotrice in Naples, and it is to be considered, with After the Duel (Turin, Civic Gallery of Modern Art: ibid., pp. 95 s. n. 2), as an incunabulum of Mancini's poetics, rich in pictorial means and strongly evocative in thematic choices. As a prodigious testing ground for the sixteen-year-old artist, it was also immediately admired by Lista and Filippo Palizzi, who saw it in Mancini's first studio, set up "in the attic of a nearby house" (Santoro, p. 257), in vicolo S. Gregorio Armeno. With this kind of production, the preference for the depiction of Neapolitan street urchins began, whose childhood denied by the miserable living conditions is described with intense realism and at the same time transfigured in a mythical key. The intimate moral identification with the world of the excluded does not, however, imply adherence to the expressive cadences proper to social denunciation, but rather becomes a vehicle for poetic and psychological sublimation (see Carminella, 1870: Rome, National Gallery of Modern Art; Il prevetariello, 1870: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte; Il cantore, 1872: The Hague, H.W. Mesdag National Museum; Saltimbanco, 1872: New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Bacco, 1874: Milan, National Museum of Science and Technology). At the beginning of the eighth decade, in the wake of the good successes at the Institute of Fine Arts - in 1870 he obtained the first prize for painting; the following year, that of figure drawing with Dressing the Nudes (Naples, Academy of Fine Arts) - and thanks to the interest of Antonio Lepre, a doctor and anatomy teacher in the same institute, Mancini obtained some rooms in the former convent of the Church of S. Andrea delle Monache, which he used as a studio together with Gemito, the sculptor Michele La Spina of Acireale, and the painter Vincenzo Volpe. There, in 1871, he produced the Figure with Flowers in Her Hair, which, exhibited at the Promotrice in Naples, made him known to the Belgian musician Albert Cahen, who requested a replica of it. Younger brother of Édouard, an influential financier based in Rome, Albert Cahen soon became a true patron for Mancini; this is the first of those numerous patronage bonds that would constitute a constant in the artist's entire professional career, characterizing his relationship with the client - always conditioned by a material dependence now unusual for the times - in a strongly anti-modern key (Rosazza). Through Cahen, Mancini came into contact with personalities from cosmopolitan cultured society (among others, the writer Paul Bourget and the Curtis family) who greatly appreciated and supported his production. After the failure of the attempt to bring Mancini closer to the German merchant G. Reitlinger, a supporter of other southern painters, Cahen provided Mancini with contacts with the international art market, allowing him to send paintings to Alphonse Portier, who managed to guarantee the sale of some works. Also through Cahen, Mancini gained access to the Parisian Salons, where he sent Dernier sommeil and Enfant allant à l'école in 1872 and Orfanella (Amsterdam, National Museum) in 1873, which had already been rejected, due to its large size, by Giuseppe Verdi, who had seen it in Naples (Santoro, p. 257). The first important study trip dates back to 1873: in May he visited Venice, where he reached Cahen, and subsequently Milan, at whose National Exhibition of Fine Arts he exhibited two small-format works initially discarded by the commission but then re-inserted into the exhibition in places of honor by the organizer Eleuterio Pagliano. In the summer of 1874, with Gemito, Michetti, and Eduardo Dalbono, Mancini assiduously frequented the Arata villa in Portici, where from July he resided with Mariano Fortuny's family in the months immediately before Fortuny's sudden death, which occurred in Rome on November 14 of that year (Picone Petrusa, p. 426). The encounter, fundamental - as for the other Neapolitan artists - because of the extraordinary pictorial and aesthetic suggestions triggered by the frequentation of the Spanish master, represented for Mancini the possibility of finally being known by Adolphe Goupil, the famous French merchant and supporter of the most lively pictorial and decorative talents of the moment. The work Jeune Garçon tenant une pièce de monnaie from 1873-74 (Naples, FL, Gilgore Collection: A chisel and a brush, p. 70 n. 18), a gift from Mancini to Fortuny, was, in fact, part of the famous auction of the Spanish artist's collection, held in Paris in 1875 under the care of Goupil. Following this opportunity for strong visibility, Mancini was urged to go to Paris, where he stayed from May to September (1875) and where he had the opportunity to meet and frequent not only the Italian artists active in the French capital, such as G. De Nittis and Giovanni Boldini, but also Ernest Meissonier and Jean-Léon Gérôme. From the Parisian merchant, Mancini obtained a contract that would allow him not to reside in Paris but to send works from Naples; although in the catalog of the 1876 Salon, where Le Petit écolier (Paris, Musée d'Orsay) was exhibited, he is resident at Goupil's, Mancini was in fact back in Naples that year. An unsuccessful attempt to open a market in Rome (where he stayed briefly with the Artists' Club) and, above all, the poor success at the Neapolitan National Exhibition of 1877 (where he exhibited Love thy neighbor as thyself and The children of a worker) led him, however, to try a new experience in France, and in March 1877 he was back in Paris with Gemito. According to what Cecchi (pp. 85 s.) reported, Mancini brought with him to France the most significant of the paintings dedicated to depicting Neapolitan street urchins, the Saltimbanco (Philadelphia, Museum of Art, Jordan legacy) in costume with a peacock feather, executed in Naples "in the shadow of a candle directed by Gemito" and a masterpiece of extraordinary poetic synthesis by the artist. Arriving damaged in Paris, the painting was retouched by Mancini himself (1878), who for this purpose had Luigi Gianchetti, known as Luigiello, a young street urchin who had become his favorite model, come from Naples. The tightrope walker, initially purchased by Cahen, was then exhibited at the Italian section of the Universal Exhibition of 1878 and purchased there by the Exhibition committee (Antonio Mancini, p. 101 n. 13). The economic pact that Mancini made in Paris with Gemito dates to these years, a sort of protectionist agreement that should have prevented both from selling their works without the other's consent regarding the sale price. This pact, disadvantageous for both, generated a series of bitter contrasts that culminated, in 1878, in the painful rupture of his friendship with the sculptor. The disagreements with Gemito, moreover, were prodrome of a general spoilage of the Parisian experience, marred by debts, diseases as well as by the tiring insertion into the demanding environments of local sociability. With the bitterness of a personal failure, Mancini therefore returned to Naples in March 1878. The already precarious psychic equilibrium was definitively disturbed in the following months, and, although continuing to paint (The Coral Seller; Pawnshop; For Sale), Mancini became subject to repeated nervous breakdowns (Oliverio). Entrusted to the care of Professor Giuseppe Buonomo In 1881, he was interned in the provincial mental hospital in Naples. Even in the months spent in the mental hospital, from October 1881 to February 1882, Mancini did not stop painting; the Portrait of Dr. Buonomo, the Portrait of Dr. Cera, several portraits of mental hospital staff, as well as numerous self-portraits - a genre in which he never tire of trying his hand - in which Mancini scrutinized himself with acuteness in a sort of ruthless autobiography of his psychic states (Antonio Mancini, pp. 104 s. n. 19, 116 s. nn. 41 s.). Testimony to his state of turmoil is also an overflowing graphomania that manifested itself in endless and disconnected letters sent to friends and acquaintances (partially consultable only in Santoro). Released from the care institutions and financially helped by Baron Carlo Chiarandà, Mancini decided to leave Naples for Rome, a city to which he moved permanently in 1883, also supported by a small monthly allowance offered by the Institute of Fine Arts through the efforts of Palizzi and Morelli. Also dating back to 1883 is the beginning of the partnership with Marquis Giorgio Capranica del Grillo, son of Giuliano and the actress Adelaide Ristori (in 1889 he painted his portrait, now in the National Gallery in London), a leading exponent of the Roman cultural environment, who became his patron and guardian. Shortly thereafter, he met Daniel Sargent Curtis, a wealthy American patron who settled in Venice in Palazzo Barbaro, and his son, the painter Ralph Wormsley Curtis, cousin of John Singer Sargent; with the works sent for their Venetian residence, Mancini entered the circle of foreign collectors residing in Italy, an important source of commissions throughout his life. This was followed by the meeting with the sculptor Thomas Waldo Story, son of the more famous William Wetmore Story, an American who had settled permanently in Rome since 1851, who offered him the opportunity to work in his studio, located in the family palace in Via San Martino della Battaglia. The relationship with the marine painter, banker and Dutch patron Hendrik Willem Mesdag, who from 1885 began to collect Mancini's works, now mostly collected in the museum of the same name in The Hague (such as The Naked Boy of 1885: Pennock and Italie), remained always a relationship at a distance. In 1887, present in Venice for the National Exhibition, Mancini frequented the salon of Palazzo Barbaro, where the Curtis entertained a cultural cenacle. Back in Rome, Mancini experimented in an increasingly conscious way with the system of the so-called double grid, consisting of a pair of string-squared frames, placed in front of the model and in front of the canvas to ensure the accuracy of the perspective layout. Left visible below the pictorial matter, it gave rise to the well-kno